Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (pBFT)

It has been argued that implementing a consensus fully based on an asynchronous system is not possible, in the work of M. Fischer, N. Lynch, and M. Paterson, “Impossibility of Distributed Consensus With One Faulty Process”, in the Journal of the ACM, in 1985.

In this sense, we must rely on a basic notion of synchrony for providing liveness.

possible [9]. We guarantee liveness, i.e., clients

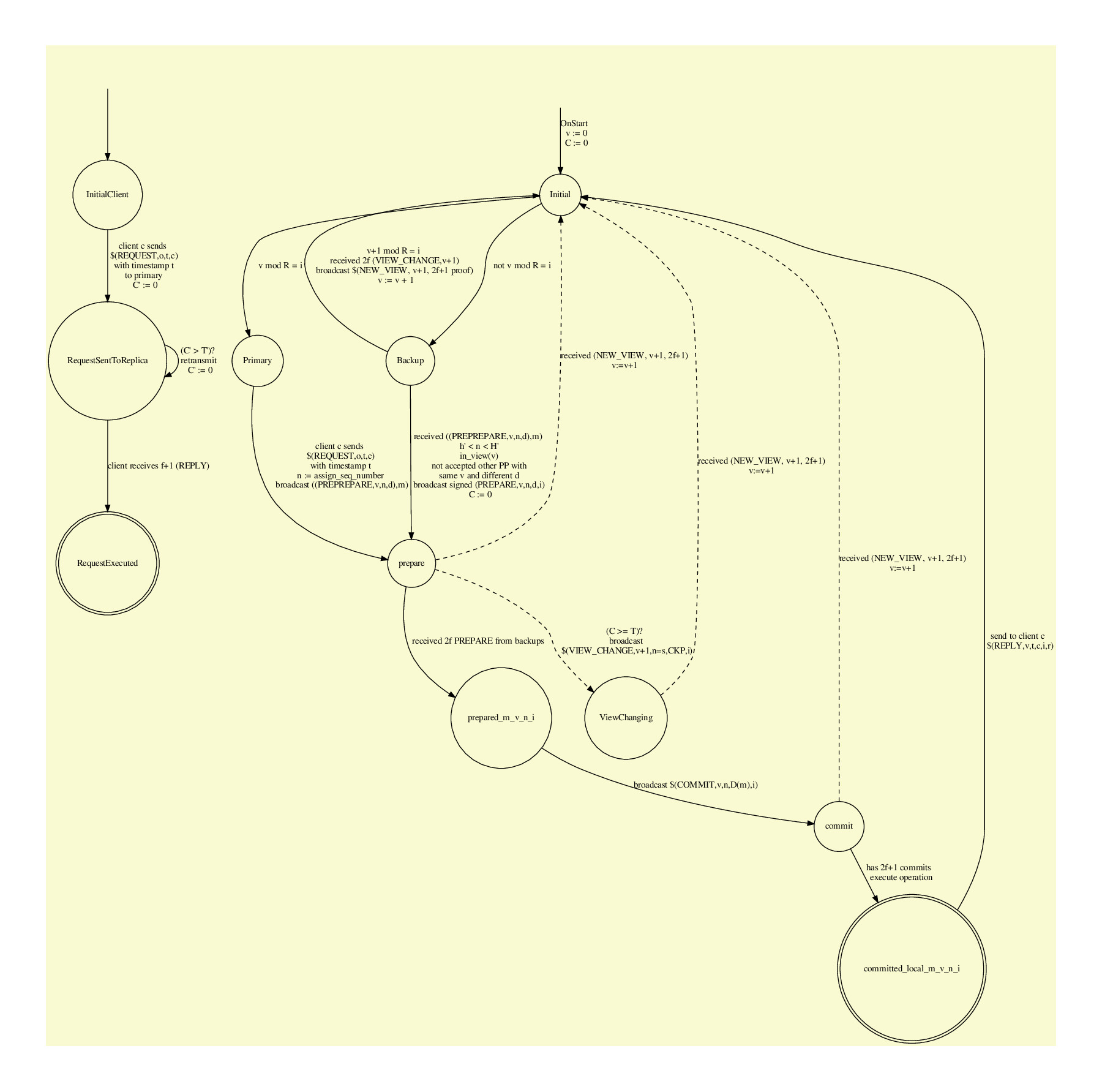

A brief summary of the pBFT follows of states can be seen in the  .

.

pBFT was designed for….

Delegated Byzantine Fault Tolerance (dBFT)

Disclaimer: Part of the content of this tutorial has been extracted from the dBFT formal specification.

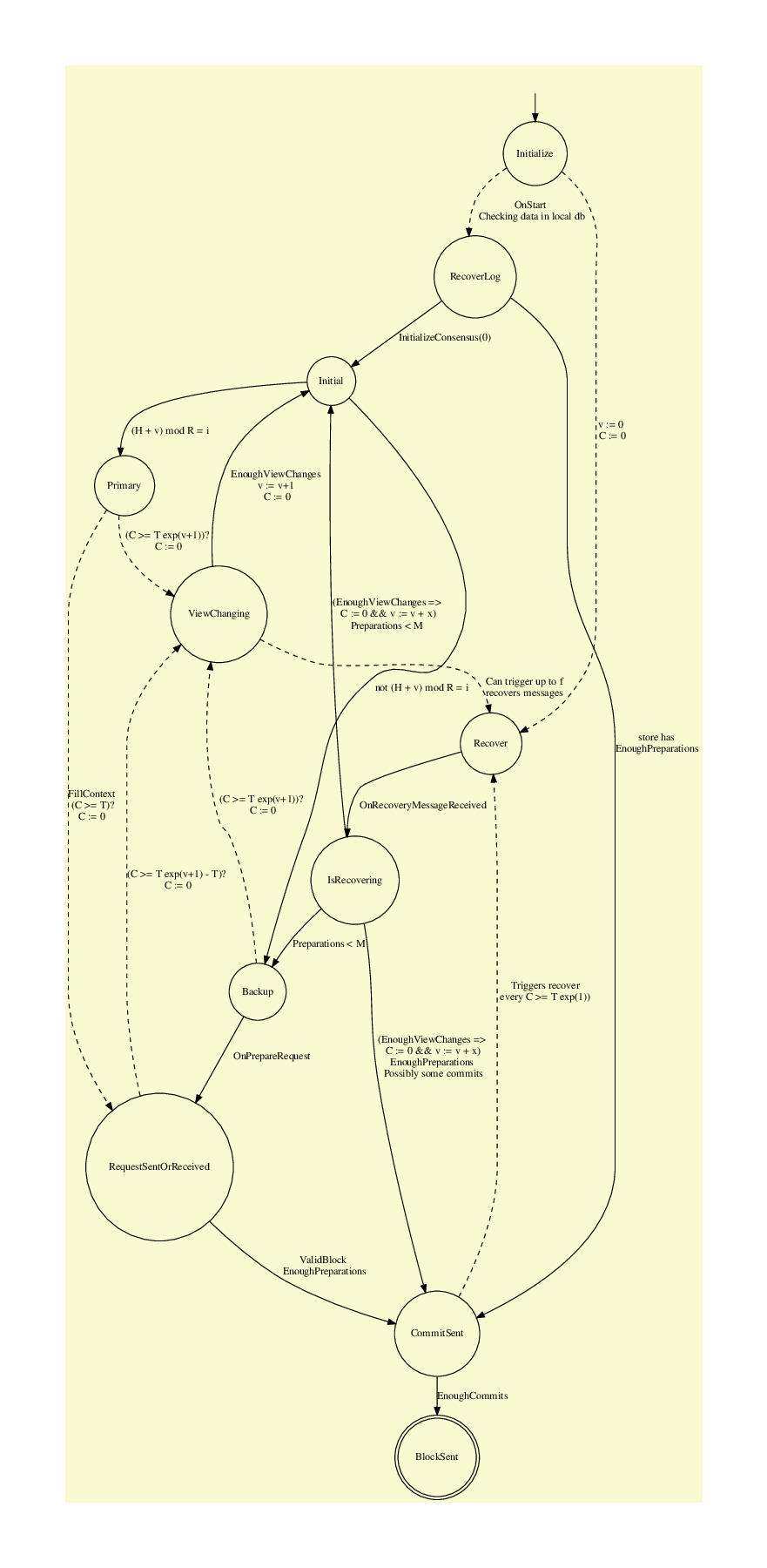

While the previous aforementioned liveness was proved for pBFT, the scenario in which dBFT works is a real-word large-scale public blockchain with state machine replication. The nature of the information shared is different and information can not be leaked. This required a refined and precisely designed recovery mechanism to be created for dBFT.

The current dBFT 2.0 flow of states can be seen below:

One-block finality

One block finality offers significant advantages for real-world applications. For example, end users, merchants, and exchanges can be confident that their transactions were definitively processed and settled, with no chance for them to be reverted. While the NEO blockchain has been designed for hosting Decentralized Applications (DApps), it is noteworthy that persisting SC transactions, which involves State Machine Replication (SMR) and is the core functionality of several DApps, poses a unique set of challenges. Maintaining block finality is a difficult task, as consensus nodes may not expose and reveal the information of duplicated blocks. Due to this, block signatures should be only provided when the majority of consensus nodes are already in an agreement.

This problem has been called as the indefatigable miners problem (defined below):

- The speaker is a Geological Engineer who is searching for a place to dig for Kryptonite;

- He proposes a geographical location (coordinates to dig);

- The majority (

Mguys) agrees with the coordinates (with their partial signatures); - Time to dig! The miners will now dig until they really find Kryptonite (no other location will be accepted to be dug until Kryptonite is found). Kryptonite is an infinitely divisible crystal, thus as soon as one miner finds some, he will share the Kryptonite so that everyone will have a piece to submit, finishing their contract (3.);

- If one of the miners dies, it will resurrect, see the agreement it previously signed (3.), and will automatically start to dig again. The other miners will suffer the same, and also receive hidden messages saying that they should also dig.

Blocking changing views and giving the network extra time

For preserving liveness, and additional property needed to be ensured:

- Nodes should be blocked to commit their signatures if they do not believe in the current network topology (asked

change_view).

However, in practice, summed up with the Commit phase locking, the dBFT had lost liveness in some case in which nodes were just with network problems. A workaround for this problem was to introduce a counting mechanism for checking committed nodes (easy to check) and failed nodes (those that you have not been in touch in the last blocks). This mechanism ensured an extra layer of protection before asking for changing view.

Along with this, another strategy that has been designed was to avoid change_views when nodes are seeing progress on the network.

In this sense, each time that nodes shared signed information between them, extra timeout are added to their internal timers, summarizing that nodes are reaching agreements and communicating between them.